Music is Ilona Tamilina’s life, until she, along with millions of Ukrainians, has to flee the war. Now that the musicologist is starting to find her feet in the Netherlands, her dream is to find a job in her own field.

Late in the evening of the 23rd of February 2022, Ilona Tamilina (37) is on the phone with a journalist from the BBC. He is curious to learn how the National Philharmonic of Ukraine, where Ilona works as a press secretary, operates under the looming threat of war. Ilona is happy to help him, she loves her job. Being around live music every day is the best the dedicated musicologist can wish for. She enjoys introducing new visitors to classical music and providing enthusiasts with the best possible information. Ilona promises to take the journalist along to the orchestra rehearsals the next day. The day turns out differently.

The next morning, when Russian tanks are rolling into the country and countless cruise missiles are shelling her city, Ilona doesn’t wake from the air raid alarm. Even though she was aware of the speculations about an imminent Russian attack, she didn’t quite believe in it, Ilona recounts. Only when she’s making her usual cup of coffee in her apartment in Kyiv’s city centre does she notice the missed calls from family and friends on her phone. “I called my mother first, and then my manager. He said: ‘Ilona, leave Kyiv. There’s a war going on’.”

“Ilona, leave Kyiv. There’s a war going on”

Ilona doesn’t want to flee. ‘Why should I?’ she thinks. ‘It’s my country.’ Carrying a sleeping mat, some clothes, and important documents, Ilona and her boyfriend Arsenii join the throngs of people in the underground metro station. “I was very scared that night,” she recalls. “We tried to sleep, but didn’t manage to very well.” After that first night, Ilona and Arsenii move to an underground parking garage closer to home. Ilona goes home during the day every now and then to shower or fetch some food. She’s afraid to stay for very long. In the parking garage she and her boyfriend barely sleep either. “We slept in all of our clothes because of the cold and so that we could flee to a lower floor in case of an attack.”

Two small backpacks

After three weeks in the garage, the continued air attacks get too much for Ilona. “The walls shook and I could hear explosions all the time. I thought: if I don’t go now, I won’t be able to later.” She decides to leave for a friend in Lviv, in Western-Ukraine. Her boyfriend is worried about family in Bucha and stays in Kyiv. Carrying two small backpacks filled with her laptop, a few items of clothing, and the memoir of one of her favourite writers, linguist George Yurii Shevelov, Ilona embarks on a twelve hour long journey on an unlit train. In Lviv, a big disappointment awaits her. Just after her arrival at the station, the air raid alarm sounds there, too. Ilona can hardly believe it.

She can’t stay in Lviv, she decides. A friend tells her about the Dutch people offering humanitarian help nearby. Two of them, mother and daughter Ineke and Elsbeth, offer her a ride to the Netherlands. Ilona leaves one of her backpacks at a friend’s house, convinced she will return in two months at most.

“The first months in the Netherlands felt like a film”

Matthäus Passion in TivoliVredenburg

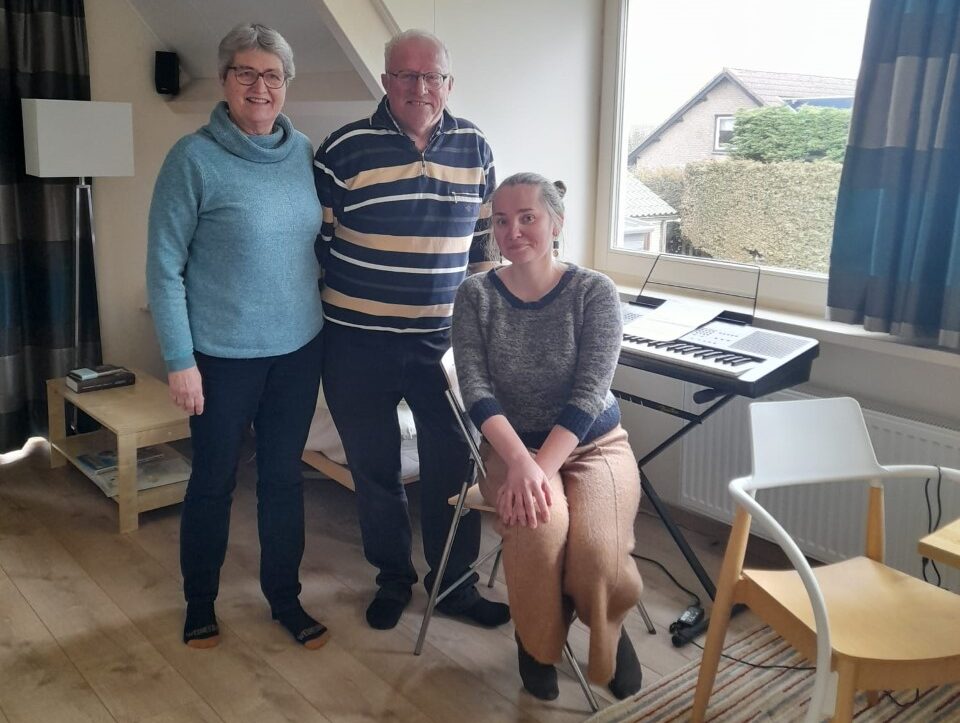

Ilona has an open face, no make-up, and waist-length hair, worn in a simple ponytail. She wears a necklace from the Carpathians, a mountain range crossing the west of Ukraine. She’s soft spoken, occasionally heaves a deep sigh, and repeatedly expresses her gratitude for the Dutch people that helped her, including her current hosts, Jacob and Marijke van der Zwan, and the chance to tell her story. She recounts the scariest moments with a timid smile in her voice.

“The first months in the Netherlands felt like a film,” Ilona remembers. “I did try to listen to music, but couldn’t focus.” Then Ineke, her host Elsbeth’s mother, takes her to the Matthäus Passion in TivoliVredenburg. Here, Ilona hears live music again, for the first time in months. “It was incredible. I recognised the concert hall from videos I had looked up in Ukraine for my job. Now I was there. A dream.”

“We’re still alive, that’s the most important thing”

Her flight feels like a pause in her career that was forced upon her, Ilona states. After several months here, she, like many other Ukrainians who have fled, has found work in the catering industry. She’s glad to be able to send some money to family members in Ukraine who can’t work because of the war. “We’re still alive, that’s the most important thing,” she explains. “Now that I’ve felt the vulnerability of that moment when everything can be taken away from you, even your life, I try to enjoy every minute.” She learns to ride a bike, visits museums and practices Dutch. She does miss the music, however.

A life connected with music

“I started to play the piano when I was seven. From then on, my life has been connected with music,” she says. She graduates from a music-focused secondary school and subsequently the conservatoire. She then earns a PhD in music history. She works as a press secretary, scientific researcher, journalist and teacher for the Ukrainian Central State Archive – Museum of Literature and Arts, the Ukrainian Radio 1, the Kyiv Academic Theatre for Drama and Comedy and the National Philharmonic of Ukraine among others.

Classical music brings an entire world to life

Sat upright and with a slightly louder voice, Ilona explains the beauty of studying historical music. “When you open a partiture, you just see graphic symbols. Only once you learn to understand those, it becomes a book you can read. You can study different layers: the artistic intentions of the composer, but also the time in which the music was written and the way those classical works are being interpreted by contemporary musicians. Classical music brings an entire world to life.”

Even though the National Philharmonic is offering performances again, Ilona feels the situation in Kyiv is too dangerous to return there. A position in her own field in the Netherlands would therefore be ‘fantastic’, Ilona muses. A careful smile appears on her face. “When I listen to classical pieces of music, I briefly feel like myself again.”

Oekraïense vluchtelingen in Nederland hebben sinds 1 april 2022 geen werkvergunning meer nodig om te mogen werken. Wel moet hun werkgever bij UWV aangeven iemand in dienst te hebben genomen op basis van deze vrijstelling. Volgens het CBS had 46 procent van de circa 65 duizend vluchtelingen uit Oekraïne tussen de 15 en 65 jaar die hier op 1 november 2022 verbleven, betaald werk. De meesten van hen werken via uitzendbureaus en in de horeca. |